Forget blame by the ‘hindsight police’. A simple tool can grow your confidence in making decisions when it really matters, explains RSSB senior human factors specialist Charlotte Kaul.

Operational decision-making gets things moving. But even with years of experience and knowledge, you might not feel able to use your own judgement when you find yourself in a situation outside of the rule book. Rules and processes are meant to help things progress, safely and efficiently. Sometimes they have the opposite effect though, and mean people are scared to take a decision. Not deciding can make a situation more dangerous. As time goes by without a decision, it can get worse. Making a decision is also risky if you only base it on ‘gut instinct’.

Even if you know all the rules, it might not be clear what you should do. The rules may conflict in your situation. Decisions are pushed up the chain of command because no one wants the ‘hindsight police’ to judge or blame them. Sometimes people judge our decisions after the situation, when they have all the right information and time to review it, but these might not have been available when the decision was made. But it’s not helpful for only a couple of people to be accountable for decisions. Things get missed or forgotten. Choices become less rational, more instinctive, and work is less safe. The more people on the team that are comfortable with making a safe decision, the better.

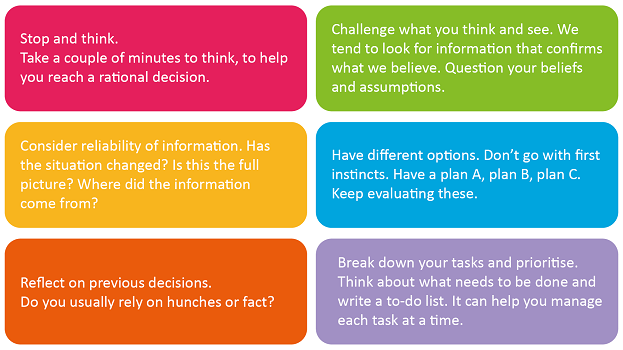

Take a look at these top tips for decision-making and the G-FORCE tool for ideas on moving forward with your decision

RSSB developed the new G-FORCE tool by speaking to railway staff and exploring what happens in other safety-critical industries including aviation, emergency services and the military.

It’s for when:

- no rule covers the situation you’re in

- you’re supposed to contact somebody for permission to act, but you can’t get hold of them

- more than one rule could be applied but these conflict with each other

- there is a rule telling you what to do, but something unusual about the situation means you can’t apply it, or if you did it would lead to an unsafe outcome.

For example:

A train has overrun the station by one set of doors. There is no selective door opening and the train cannot set back. The train is full and standing and lots of passengers have luggage and pushchairs. Company policy is to open one local door. What would you do as the train driver?

Here’s how it works

Go or no-go – Is there a rule or procedure that could be followed? If so, follow it. If there isn’t one or for some reason it can’t be applied, then go to the next step.

Facts – Gather all the relevant information, such as: time of day, weather conditions, whether people are trapped on trains and their comfort level. This is the most important part of decision-making. Find a balance between getting as much information as you can and acting in a timely manner.

Options – Based on the facts, consider the options available. Come up with a few.

Risks – Consider the potential consequences for each option. What are the risks to you, other staff and the public? Are there wider system risks?

Choose – Decide the best option. If there are multiple safe options, which would cause the least delay? You may choose more than one, such as plans A, B and C.

Evaluate – As the event unfolds, consider whether the option you chose is still the best one. Be ready to change your approach if needed. After the event, can you or your company learn from it?

More information

WATCH: Charlotte talks decision-making and G-FORCE

G-FORCE tool and training (T1135)

Email G-FORCE