With CIRAS turning 25, Greg Morse looks back at its origins in light of the historical evolution of safety culture on Britain's railway.

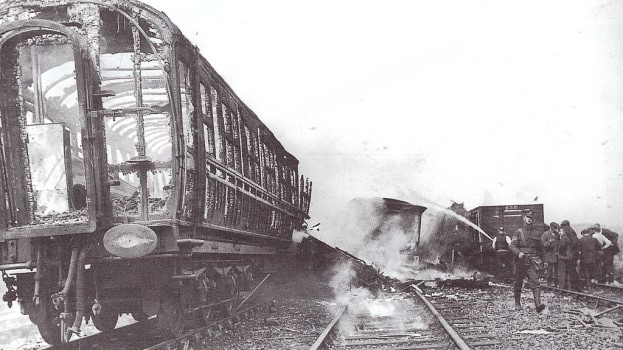

Imagine a time when the operator – the frontliner – got the blame for everything. Britain’s worst railway accident came in 1915, when a multi-train collision led to the deaths of over 200 people, many of them soldiers on their way to Gallipoli.

If you’ve read The Quintinshill Conspiracy by Adrian Searle and Jack Richards, you might have concluded that collusion put all the blame on the signallers that fateful day. It’s certainly true that they made mistakes and bent the rules. But it’s also true that there were many different holes in many different defences that led to it, making it a classic illustration of James Reason’s famous Swiss cheese model of accident causation.

Above: Quintinshill, 1915

What happened in 1915 was in some ways part of the culture of the period – a culture that the Great War would help to erode. By 1989, everything would be as open as one would hope it to be…wouldn’t it? Sadly not. It was on 4 March that year that a passenger train passed a signal at danger (SPAD) and struck another crossing its path at Purley in South London. Five people were killed and 88 were injured. Pilloried in the press, the driver – Robert Morgan – was later sentenced to 18 months in prison. The simple truth about the accident, though, was that the truth was not nearly so simple. The signal in question had in fact been passed at danger four times before. One incident had involved a brake failure, but at least two of the other three had been ‘Purleys in the making’: SPADs in which the driver had continued past a ‘red’ despite having received automatic warning system alerts in the run up to it.

These drivers, like Morgan, had made mistakes, but part of the problem lie in the positioning of the signal. Drivers might have been afforded slightly longer to see it while in motion than the seven seconds considered acceptable for a 90 mph line, but it became obscured by the station buildings as trains approached. So signal sighting was another hole in another Swiss cheese slice. It was considered ‘new evidence’. It was accepted by the court in 2007 and the conviction overturned. Sadly, Morgan would live for just two more years with his name cleared.

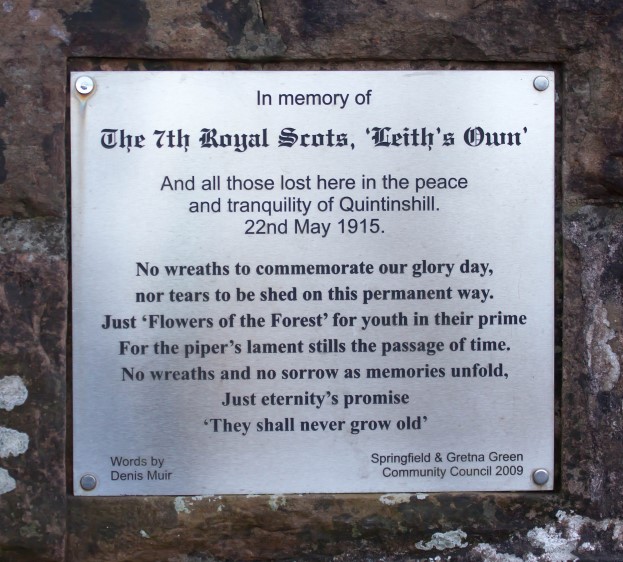

Above: Site of the Quintinshill rail accident, in more recent times

What was missing at Quintinshill and at Purley was a deeper understanding of what we now call human factors, or why people do the things they do. It was in Scotland that the first serious move was made to address this issue, ScotRail having commissioned a report following the Greenock accident in 1994, which showed that many incidents were associated with human error. As a result, the operator awarded a grant to the University of Strathclyde to research the role of human factors in accidents and near misses on the rail network.

The university developed a prototype CIRAS system, which was designed to classify reports received from train drivers, guards, signalling staff, maintenance staff and railway management. The idea was to gain an insight into the weaker signals, the ‘accidents waiting to happen’. As many staff members at that time would have been less than willing to report against their own companies, confidentiality was a key element. This helped ensure that the Strathclyde system worked. Its future looked bright. Then came another accident.

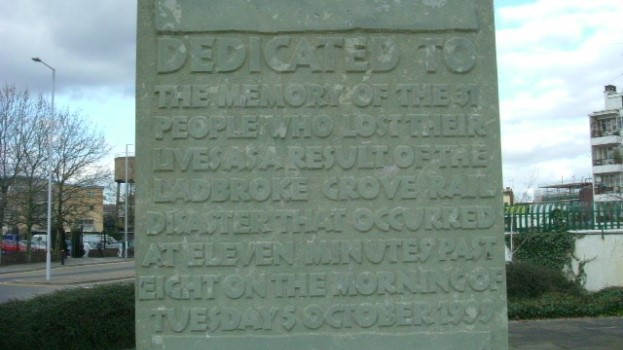

At around 08:09 on 5 October 1999, a commuter train bound for Bedwyn passed a signal at danger and struck a high-speed train as it made for Paddington. Thirty-one people were killed and over 500 were injured.

One of Britain’s worst peacetime accidents, it was subject to a public inquiry, led by Lord Cullen, who’d also looked into the 1988 Piper Alpha oil rig disaster – an appropriate choice, as many would come to think of Ladbroke Grove as the railway’s equivalent of that multi-causal tragedy.

Above: Ladbroke Grove memorial

Cullen’s report would highlight problems with signal sighting, train protection, train crashworthiness, driver training and learning from operational experience. But there was something else, and it concerned reporting. More specifically, it concerned the need for a ‘no blame’ culture.

The Health & Safety Executive had been encouraging rail to adopt such a culture in the hope it’d ensure that all incidents, including near misses, were reported and investigated without fear of punishment or criticism. The trouble was, it seemed to encourage too many drivers to take the blame for SPADs when there may have been other factors at play. SPADs are traumatic incidents for drivers, and it was felt that many were holding their hands up just to get the investigation over as quickly as possible. Indeed, 85% of SPADs at the time were listed as being down to ‘driver error’. With a figure that high, it was likely that many underlying causes were going unrecorded.

At a time when internal reporting procedures were often associated with blame and disciplinary action, CIRAS allowed reporters to speak freely without fear of reprisals. Cullen hoped that – one day – ‘the culture of the industry would be such as to make confidential reporting unnecessary’. But he knew that day was a long way off, knew too that CIRAS could help root out underlying issues by helping near misses to be reported and the trends associated with them to be measured. He duly gave CIRAS his full encouragement and support.

As a consequence, CIRAS was adopted by all UK mainline rail operators. Its value is now recognised more widely across the transport sector, with its use spanning bus, tram, metro and the infrastructure supply chain.

CIRAS remains a vital means for capturing knowledge from those who get their hands dirty. In this, it helps build a solid foundation for shared learning across different sectors. It also helps shine a light on dark pockets of risk, a clear case in point being the railways’ growing understanding of road risk, which was relatively unknown until CIRAS stepped in to help pave the way. Indeed, as a direct result of CIRAS activity, the rail industry now has a dedicated Road Risk Group, while occupational road risk management is one of the key risk areas in the Leading Health and Safety on Britain’s Railway strategy.

With CIRAS now turning 25, one can look back to Cullen’s hope that one day it wouldn’t be necessary. But real life is real life, and real people are real people. The world is not an ideal place, so there will always be a need for the confidentiality that the service offers. And anyway, who would have thought in 1999 that in 2021 we would be suffering from an unprecedented pandemic, a pandemic which has killed over 100,000 people in Britain alone?

When people are afraid, many don’t want to show it, and when times really are unprecedented, many more genuinely do not know what to do for the best. Many of the reports to CIRAS over the last 18 months or so have related to Covid-19. Those reports will have helped the reporters, but helped the rest of us too, by highlighting concerns which in turn will have fed into risk analyses and mitigation methods: key work in a key industry, particularly in the face of new and changing risk.

In the future, we’re going to need to go on expecting the unexpected. CIRAS will help us do that. Long may it continue.

Above: Quintinshill memorial

Tags

- Confidential reporting

- Culture