Why don’t people always listen effectively? How can we overcome safety silence? Director of CIRAS Catherine Baker explored this in a talk at the Safety & Health Expo.

CIRAS’ Catherine Baker spoke to an audience of health and safety specialists at Safety & Health Expo, sharing her thoughts on listening gaps and how we can all make sure people are heard.

How listening makes a difference to safety

‘Both speaking and listening are critical, but a culture of silence can grow if left unchecked,’ Catherine emphasised. ‘If you take a handful of accident reports from any industry, you won't have to look far to find evidence of safety silence.’

For example, Catherine referenced three recent incidents where somebody knew there was an issue before they happened. One from the Marine Accident Investigation Branch safety digest in April 2022, in which a coaster bulk carrier collided with a quay on approach to berth: the pilot thought the speed was slightly high just before the turn but did not raise a concern about this live hazard, which could have changed the course of the accident.

Another was the derailment at Carmont on 12 August 2020, in which three people sadly lost their lives. The Rail Accident and Investigation Branch (RAIB) cited erosion being visible when Network Rail and Carillion staff inspected the site in March 2013. RAIB said, ‘This was a missed opportunity to recognise the effect of the bund on water flows.’ The implication is that the asset may have been a visible hazard but either people didn’t realise the seriousness of what they saw or did not raise it in a way that was heard.

And an RAIB report into a trackworker fatality in April 2020 said, ‘Evidence suggests that the trackworker did not always follow rules, standards and procedures, and had become habituated to warnings from approaching trains,’ but that no close calls were raised. People had noticed and challenged unsafe behaviours, but this was not escalated when nothing changed.

The conclusion, Catherine said, is that often the knowledge to prevent an accident exists, just not with the right people. Looking back at CIRAS’ own history: the investigation into the rail accident at Ladbroke Grove in 1999 highlighted the need for people to be able to raise concerns about underlying issues and near misses. This was the catalyst for CIRAS becoming a national system for the railway in Britain, and since then our reach has extended more broadly across transport and infrastructure.

Cultural issues

Catherine also talked about endemic safety silence, often highlighting larger cultural issues within organisations.

Quoting from an RAIB annual report 2020, referring to a Signal Passed at Danger incident in Loughborough: ‘There was a gap between documented safety processes, and what was actually happening. There also appeared to be no management awareness of how well, if at all, the company was following its own safety processes … a positive, open and honest culture is also needed if leaders are to be properly informed, and protected from wishful thinking.’

She highlighted that this is a classic case of a difference between what was happening in real life and what management expected to happen based on the procedures set. Perhaps the procedures don’t account for all scenarios, or are cumbersome, so people come up with well-intentioned alternatives to get the job done. When there is no feedback loop, decision-makers are unaware of this gap between expectation and reality, and can’t use that knowledge to make the work safer. In the situation mentioned, it did not lead to an accident, but the outcome could have been very different.

Likewise, the RAIB report into a collision between two mobile elevated work platforms at Rochford revealed that, ‘Witness evidence suggests that this [perception of time pressure] led to a general feeling among OCR staff that if they raised safety issues which could lead to work within a possession being stopped, even for a short period, they would be identified as the source and criticised.’

This accident report dug deeper into why there was a safety silence, pointing to the perceived personal consequences of anyone raising safety issues that might delay the work. If you are part of a team under time pressures, even if there is supposed to be a worksafe procedure so that anyone can stop the work if they think it is unsafe, the incentives are aligned against a safe outcome.

This incident also highlighted the impact of a culture of disrespect between employees and contractors, and in particular the influence of racial prejudices. This cannot have escaped the notice of those working on site, but it took an accident for this realisation to be made visible to decision-makers, Catherine explained.

Overcoming safety silence through listening

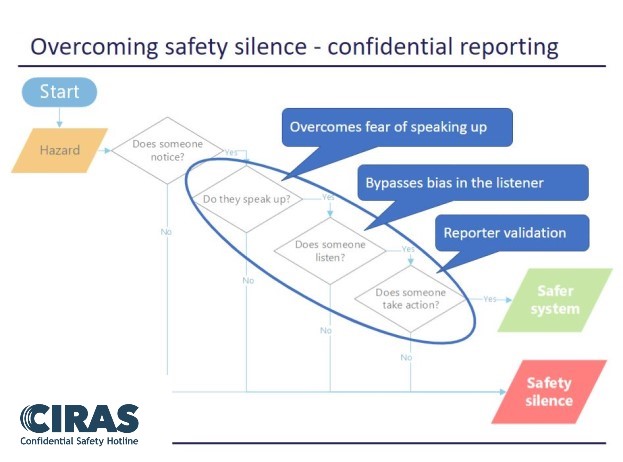

Taking a process approach, Catherine revealed a flowchart (below) that is helpful in understanding how safety silence can emerge in any organisation.

Someone has to notice the hazard or risk – and then speak up about it. Someone has to listen carefully, and then must act. There are lots of opportunities for safety silence to win.

There are two ways of cutting through the silence:

A: Stop there being a silence by ensuring information does flow through…which requires tackling all four steps.

B: Listening to the silence.

Listening inclusively (B) is about listening for the voices that you aren’t hearing from, to see what intelligence you may be missing. For example, you could compare the incidents that are happening to the concerns and ideas being reported, to see where the gaps could be. What can you learn from what you don’t hear, as well as what you do?

To achieve A – or full visibility of all the information that can help us keep systems safe – means getting all four steps of the information flow (pictured above) to work. Catherine delved into the work of Dr Mark Noort on safety silence to address this.

Barriers to raising concerns – and to listening effectively

Catherine considered some of the barriers to raising concerns, including people’s own experiences and thoughts.

If you are the newest member of the team – would that make you hesitate to say something about your concerns, in case you are wrong?

If you are already feeling 'different' in a group, as the only woman, the only person without English as a first language, the only person of a particular ethnic or cultural group, for example, then raising an issue and being noticed for it might feel difficult to do.

And yet, Catherine explained, it is the voices that are not heard as often that we really need to hear, because they could bring a new perspective that could make everyone safer.

Sometimes people are more likely to raise concerns if they know their identity is protected, such as through confidential reporting, because then they are not at risk of what they perceive as potential consequences, such as being singled out for it or even losing their job.

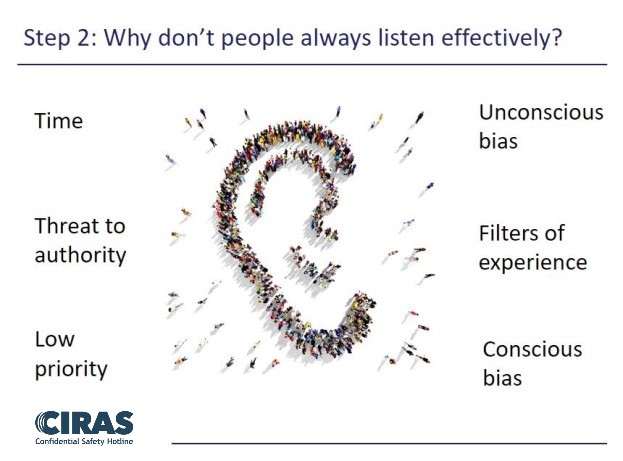

On the other hand, when people do raise concerns, conscious and unconscious bias can impact listening negatively so that it is not as effective.

In a striking example cited by Catherine, when orchestras started using blind auditions, the diversity of successful musicians in the orchestras increased. The musical abilities of women and minority groups had not improved overnight. Instead, the musical directors could only listen to the music and any filters they may have had – preconceptions or unconscious biases – were removed. They really listened, and made different choices.

In the same way, if you are responsible for a system and the processes needed to make it work so you know what ‘should’ happen, it is often instinctive to defend that rather than to hear people when they raise difficulties with how it is working in practice. This can lead to workarounds rather than real improvements.

The Deepwater Horizon oil spill – the largest marine oil spill in history – is just one of the accidents where a failure to listen played a key role.

What is conscious bias? Think about responding to an email from your manager after telling your team you are off emails while working on an important task: you are choosing who you listen to and who you don’t. We all do it. But, Catherine asked, what impact could that be having on safety?

If the temporary night cleaner mentions something to you at the end of their shift, do you give it the same credibility as you would when hearing from the qualified and experienced site director after their monthly inspection?

Or if someone flags something up which simply does not fit your worldview of what is supposed to happen, you might dismiss it – intentionally or not – without further thought.

Whether it is listening to people or listening to data – going deeper to really understand is important, said Catherine, highlighting the work of our reporting analysts at CIRAS.

The team has time to listen. They have no preconceived thinking or vested interests, so can delve deep to really understand the concern and its implications on safety, health and wellbeing.

When the concern is passed to the company, they don’t know the source, so can only focus on the content – and are less likely to be biased in their thinking.

Finally, by closing the loop and telling whoever has reported the concern what has changed, this not only improves safety but incentivises future reporting. And those positive outcomes can overcome the ‘fear’ in the listener that someone raising an issue is a threat to be defended rather than an opportunity for improvement. Listening inclusively and working to overcome safety silences makes it safer for everyone.

Find out more

Listening well can improve outcomes in times of change

Why listening can prevent safety silence

How listening can help people thrive

The power of listening in safety and wellbeing – Watch Catherine Baker's talk for the Rail Wellbeing Live event

Tags

- Culture

- Confidential reporting